search

date/time

| Cumbria Times Weekend Edition |

Paul Spalding-Mulcock

Features Writer

@MulcockPaul

8:31 AM 24th September 2021

arts

Interview With Rachel Deering

Rachel Deering

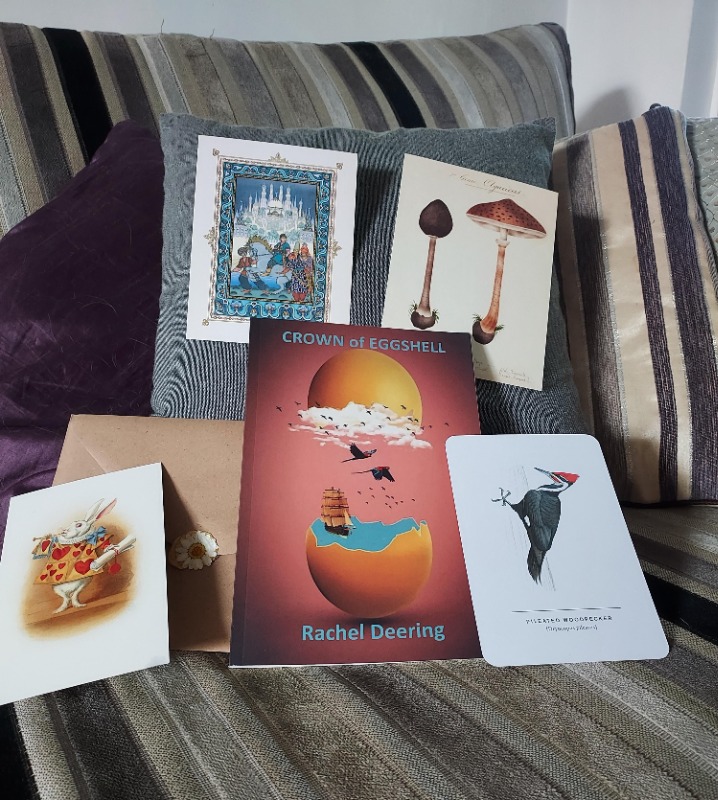

Rachel Deering is a poet epitomising this dynamic, for her path to her debut anthology of deeply personal poems has not been smooth by any standard. Crown of Eggshell blissfully melds Breton and Gallic myth with homages to a panoply of exotic and common birds, whilst orbiting the Moon itself and taking refractory meaning from deftly scribed encounters with Mercury, Mars, Jupiter and Neptune.

Structured as four self-contained vignettes, Deering has sought to attest her love of nature and cathartically employed lustrous imagery and dextrous sensitivity in order to examine the myth of her own being and the universality of decay, restoration, love and redemption. Her collection is a modulated song of the soul’s flight through both troubled and clear skies, ultimately leaving its reader conspicuously aware of life’s vacillations, like waves churning the surface of the deepest of seas.

Having recently read Deering’s visceral, yet elegantly nuanced collection, I found myself fortunate to interview her for our readers.

Deering had once been a teacher with several of her early poems published in a variety of esteemed publications. An imperative need to recalibrate her lifestyle and find balance in her personal world led to a ten year hiatus in her creative outpourings. Three years ago, she once again took up her pen and begun submitting her work to ABC Tales. In January 2020 Cerasus Poetry suggested she work upon a new collection of work and Crown of Eggshell was born.

Wanting to understand the sensitivities at play in her work, I asked her to shed light upon her personal beliefs and attitudes: ‘I am often overwhelmed and saddened by world events, how we treat one another, how we treat the world and environment that we live in. I believe very much in kindness and showing love for all things. I am deeply saddened by our disconnection from each other, from our environment, from all living things, by the level of discrimination, hatred, self-interest and corruption’.

Deering’s love of poetry began with T.S. Eliot: ‘I was particularly ensnared by T.S. Eliot, but I was already writing bad poetry by then. Iwrote my first poem when I was eight, about Autumn and then I suppose it became a natural medium for me to express my thoughts and feelings. Thankfully, I was my only reader for a long time’.

‘The poet who, no doubt, has influenced me more than most is T.S. Eliot. I was particularly struck by The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock when I was a teenager – which is odd, age-wise, considering the context of the poem, but I think I felt very sad and lost at the time, as well as being hit by the great skill of the poem. It’s almost the perfect poem as a masterclass in how to write poetry – it has everything. I love Pablo Neruda, Ted Hughes, Mary Oliver, Sylvia Plath… Mary Oliver’s Wild Geese made me feel so much less alone – I often go back to it. I think poetry can often remind us that we are not alone’.

‘For me, feeling my feet on the earth or watching the work of a bee can feel profound and moving. I have a love of metaphor, repetition of words or lines, a dash of alliteration, but I don’t really think about any of these things when I write. Maybe I should!’.

‘In terms of the development of poetic voice, I can separate my poetry life into phases: the child poet, blissfully unaware that her poetry was terrible, the teenage poet who wrote poems with the ink of tears, blissfully unaware that her poetry was terrible, the poet of her twenties who wrote profound and angry missiles, blissfully unaware that her poetry was terrible’.

‘In my late teens, early twenties, a few important things happened. I read a lot more T.S. Eliot and read that reading The Golden Bough by J.G. Frazer would help understand his poetry, The Wasteland, in particular. So I read it, and then a world fully opened up to me – Graves, The White Goddess, all the mythology I could get my mitts on, folklore. Interestingly, I suppose, this only penetrated my writing very loosely’.

‘The other major influence for me was the editing process for my collection. Quite apart from cutting out some bad habits, most importantly, my editor encouraged me to be specific – if I was making veiled reference to myth then stop and be specific, name the god you mean. I am so grateful to my editor for this because it has made me feel that I am able to write with confidence and without restraint and about the things that are meaningful to me’.

I hesitantly pressed Deering for the causative factors which led her voice to fall silent for a decade. She bravely told me: ‘I was very unhappy and felt completely shut down to any creative outlet. When I started again, this was a direct result of having therapy; as soon as I reconnected with my feelings again, I couldn’t stop writing. I had completely buried my feelings in trying to function on an entirely intellectual level and in being a workaholic - and there’s no poetry in that!’.

Perhaps the best way of understanding Deering’s creative impulse is to understand her relationship with nature: ‘I am definitely a “tree-hugger” on a walk, it can bring me to tears. I feel connected and safe and at peace, as if all of the concerns - I feel profoundly moved by all things in nature. A sense of this connection is present in me when I am outdoors, to touch a leaf or a tree, to feel my feet on the earth, the movement of water, a hare or a heron spotted, the wind, the cold in my cheeks, the song of a bird, the flutter of a bat (or cuddling my cat at home). ALL of it, I feel the ache of it in my chest and anxiety of the real world shifts away’.

Mythology also circumscribes her poetic mind: ‘I think when I discovered a world of mythology it continued the theme for me set by the fantasy fiction of my childhood. I love it. I guess I went through a very ‘biology’ phase in my twenties too – and read a lot of philosophy. I’m very fascinated by the idea of archetypes in story and myth, including the Bible. I have read a lot of Jung too and very influenced by his work’.

Also by Paul Spalding-Mulcock...

Word Of The Week : CorpusThe Gallery, Slaithwaite: ‘Ten’ - A Birthday ExhibitionWord Of The Week : SibilantWord Of The Week : PropinquityWord Of The Week : IdiosyncrasyBut what of her poetic language? ‘I think I like reflections in imagery – what does a thing reflect and is that also connected to a feeling. Similarly with metaphor, I suppose. Again, I don’t think I have an artistic desire as such – it is the expression of my feeling. I feel all of my poems in my chest and I have to find the words to frame that feeling so I try to produce the images and metaphors to give words to it. I need the metaphor, sometimes extended, to convey how something feels’.

Deering’s scintillating talent continues to bubble within her visceral soul: ‘I am working on a new collection. I hope that someone might consider publishing it! I don’t know if I can predict subjects and themes for the future – it will all depend on my feelings. I tried to explain to my therapist why I had stopped writing – I said that when I write, I see the world in a particular way, but after having therapy, I realised that it was also how I felt the world, not simply how I saw it – and I can’t predict my feelings in the future. My themes will remain largely similar, I imagine, my feelings entwined somewhere between myth and folklore and nature’.

Crown of Eggshell is published by Cerasus Poetry