search

date/time

| Cumbria Times Weekend Edition |

Artis-Ann

Features Writer

2:00 AM 25th June 2022

arts

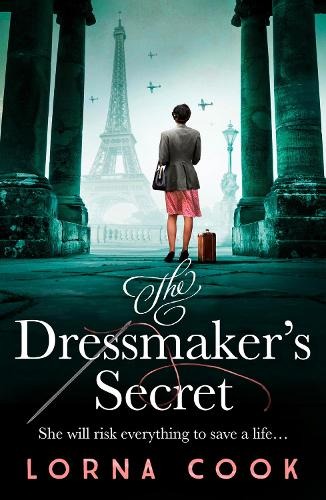

The Best And The Absolute Worst: The Dressmaker’s Secret By Lorna Cook

Inspired by information which has come to light in the last decade, The Dressmaker’s Secret tells the story of Coco Chanel’s war, as seen through the eyes of her assistant. While the details of Mademoiselle Chanel’s activities in Paris at the time of the Occupation are as accurate as documentation can make them, the assistant is a fictional character and Cook successfully interweaves fact and fiction to create an intriguing story with an authentic foundation.

Adèle is an orphan, brought up by nuns in St Nazaire and trained in secretarial skills. When she leaves the orphanage, she moves to Paris and brazenly seizes the moment when it presents itself. She becomes the personal assistant to the legendary fashion icon, Coco Chanel, whom she discovers was also brought up an orphan and has created a business – and a reputation – by honing her own survival skills. A word of warning: be careful what you wish for. Chanel’s reputation was seriously tarnished by the revelation of certain files, and LBD notwithstanding, her halo, if you thought she had one, is not left intact. Icon yes, but her behaviour will give rise to discussion between admirers of those survival skills and those who found them distasteful at the very least.

When war comes to Paris in the form of the Nazi Occupation, Chanel closes down her sewing industry saying, “War is not the time for fashion”, and maintains only the perfume and accessories elements of her range. She is a hard woman who thinks only of herself. Having sacked the majority of her staff, at a time when other boutiques kept going, she gives none of them a second thought. Every man (or woman) for herself. She does keep Adele by her side and Adèle is, at first, grateful to have a roof over her head, even if that roof is the Ritz hotel, which causes her some pangs of guilt. The music plays and the champagne flows in the decadent hotel, overrun with Nazi Officers, while those Parisians who evade capture struggle to find a loaf of bread.

Through Adèle, the reader witnesses Coco Chanel’s collaboration with Nazi Officers. “We are women”, Chanel tells Adèle, “…with no one to protect us…we must rely on ourselves for our own survival”. Her activities are made all the more shocking because they contrast so sharply with Adèle’s own experience. She meets (and falls in love with) an American doctor, working in the local hospital under the flag of the Red Cross. He also works with the French Resistance and Adèle is briefly drawn into a world where discovery will mean certain death. She rescues a child and helps deliver a package of a different sort to her native St Nazaire.

Dual timelines run parallel in this novel. Adèle’s granddaughter, Chloe, is recently divorced and has moved from London to Paris, for her own kind of gap year, to broaden her experience and to discover more about the life of her grandmother. Adèle, it seems, has not been keen to talk about her time in Paris and Chloe is intrigued and a little bit worried but determined to find out more. At an auction of property from the Ritz, she meets Étienne, an art dealer with an interest in war history, and the two discover a shared link with the past, as both seek to fill in the gaps. As the narrative unravels, it is hard to remember that one strand is wholly fictional and the other based on fact, but a vivid picture of Paris is created, both in wartime and in the present.

After the Occupation ends, and the Germans retreat in the face of the advancing American army, the horror of reprisals is made clear, not least the partisan show trials and “grotesque parades” of les collaborateures horizontals; rough justice for many women who acted only to feed, and therefore save, their families. It is noted with some subtlety that male collaborators who had bartered with the occupying forces and worked the black markets, did not suffer the same ignominy, and I have read enough in other books to believe this much was true.

Chanel was, herself, arrested but despite her associations with Nazi officers being openly flaunted at the time, no concrete proof of her actions could be found after the war, many of the files pertaining to her having been destroyed or ‘lost’. The Free French Purge Committee (FFPC) found her innocent in a rather more formal trial, and, as is well known, she went on to re-establish her business and to rebuild her empire.

Cook describes herself as writing “historical fiction, weaving secrets and pieces of forgotten history with romance and intrigue”, and in this case she has created an enthralling account which has it all, and which entertains a neat little twist at the end.

The Dressmaker’s Secret is published by Avon