search

date/time

| Cumbria Times A Voice of the Free Press |

Steve Whitaker

Features Writer

@stevewhitaker1.bsky.social

12:00 AM 13th September 2025

arts

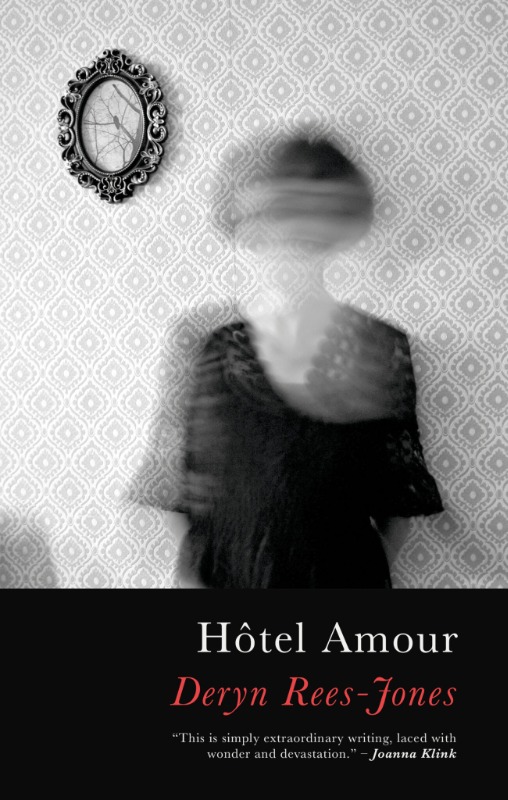

Along The River's Lines: Hôtel Amour By Deryn Rees-Jones

And if, in Hôtel Amour, lack of focus is almost a métier, then Rees-Jones employs an adaptable framework of formal approaches to describe a fundamentally intractable stream of consciousness. The process is intriguingly diverse – the epigrammatic opening section (‘The Hotel’) is followed by an untitled series of sonnets before the narrative recourses to a concluding collection of disparate and fragmentary thoughts in ‘The Garden’. But what truly distinguishes the opening and closing sections from any inference of prose is the gorgeously florid and poetic nature of the language: beautifully conceived and written, Rees-Jones’ style is elegant, sonorous and effortlessly seductive, occupying a complex liminal space between several locations at different times, and against a profoundly affecting canvas of love and loss. The words themselves, the delicious syntax and astoundingly persuasive use of metaphor, may be relished for their own sake regardless of context, and in satisfying isolation from any narrative thrust.

The poet’s accumulative sense of purpose in the iteration of phrasing in subtly different guising works to aestheticise her mandate here, to distil moments of real Rilke-esque beauty. And if the approach is studied – Rees-Jones’ extensive research, as evidenced in her acknowledgments pages, is visible in subtle derivation, and in nods and winks to a host of writers - then her narrative remains thoroughly soaked in the surreal historical purlieus of a Parisian landscape whose eponymous hotel we half-recognise through a prismatic imaginative glass. Rees-Jones’ imaging is varifocal to the degree that each ‘reverie’ may disclose several inferences: captured in a ‘Brown Study’, the unnamed female protagonist, here observed in the third-person, conjures a tableau of meta-narrative suggestion whose presence betrays the simple unguarded randomness of the aside, yet illuminates the history of creative surrealism upon which the image also hangs, as absurdly compelling as the huge suspended pear in the Satie museum at Honfleur:

‘She glanced up and was startled to laughter when she saw a grand piano dangling in the sky on a wire as its owners tried to remove it from their fifth-floor apartment’. (From ‘The Hotel’)

If the protagonist is a Mrs Dalloway figure, struggling to assert a sense of self in a resistless tide of associations and signifiers, then her situation, her existence, is partially disclosed in disunity, as we piece together the bricolage of a life and a history with methodical irony. Indeed, Woolf seems close at hand as the compelling figure ‘shook her head as if resetting a watch’, whilst remaining, like the cat that is both real and metaphor, existentially displaced:

‘The kitten had no logical home, and so it sat there, in both sections, waiting for someone to decide where it belonged.’

The resoundingly beautiful series of sonnets that comprises the central section of Hôtel Amour opens on to a landscape of confession. Given will and sentience in the first-person, the camera is reversed as the protagonist’s disordered perception reveals a personal journey conducted from the perspective of the present, yet mediated by the inflammations of memory. The inveigling lover’s presence – he is more or less constant – acts to disturb the imaginer’s sense of time and space, to precipitate an uncoupling of signifiers, a disturbance of language and the external world. Here, the ravelling of the creative instinct with both the languid rhythms of nature, and the frenetic energy of nature’s opposite, is coaxial; the power of Rees-Jones’ words resides in possibility and a recalibration of the feint line dividing lived experience from fiction: ‘I kick / dead leaves and rhymes along the river’s lines. The digital world / continues its insistent & galaxial glow.’ (‘i’)

As the confessional flow is interrupted by a direct address to the loved figure, the present erupts into the tableau as vigorously as a shock of ECT to the narrative cortex. At her very best in imaginative thrall, Rees-Jones’ focus is both intense and intensely creative, refulgent and pyrotechnic, eliciting a sense of being in the climactic moment as palpably as Hopkins. The received effect is astonishing: discovering rapture in the quotidian, the storm’s eye in suburbia, the narrator’s awakening is epiphanic:

‘Darling, what night did we not sleep through storms together,

when thunder was like bins, rolled out by kindly neighbours,

mundane debris of the world on forecourts, in turn put out

by our un-misery? Eros. Roses. Roars. As lightning forked

and shimmered, as we stood under its bright chancery,

my chin edged to your shoulder, finger looped in your cool finger,

separate, still, by the blinded window. Look, the great elm, the cherry!’ (xvi)

Transfiguration might, as Stanley Spencer found, be actuated in the ‘mundane debris’ of bins and forecourts, or in the good offices of kindly neighbours; the electric moment’s ‘bright chancery’ – wonderful phrase – effects another kind of ministry.

‘The Garden’ returns the central figure to the occluding soft focus of the third-person, and a strange concatenation of random observations, locators of contemporary meaning that anchor the narrative in a profoundly unsteady present. The camera, here, is handheld, disturbing focus, as if time were disobedient to the rules of linear arrangement. As elsewhere, Rees-Jones’ figurative skill nails the sense of hanging on with impeccable brevity:

‘Time shook the seasons and something like a snow globe on freeze-frame

halted and refused to recalibrate.’

The snow globe’s recalcitrance is one symptom of a loss of control, an inability to mitigate the free-flow of images and blandishments that blossom in the tableau’s unfolding. Another is the direct assault of memory, the immersion of the dead (both known and unknown) into the realm of the imaginer:

‘sometimes, the dead wandered into the house, congenially threw them-

selves down in a chair with all the force of habit and expectation she had

come to know when they were alive. Sometimes the elsewhere dead came,

too, from their cars or unsafe houses, riddled with bullets, or with breath

taken from them, flames in their clothes or hair.’

These last, these ‘elsewhere dead’, are visitants, a reminder of the extraneous ‘elsewhere’ whose evisceration affects us only through the detached lens of several removes, yet whose meaning is, or should be, as palpable and horrific as the shell-obliterated ghost of Evans in the guilt-ridden imagination of Woolf’s Septimus Warren Smith.

This contradiction of ghosts is a reminder, too, of the presence of opposing binaries throughout Rees-Jones’ resistlessly changeful narrative. And yet there is a kind of consistency in the inconsistent nature of her exposition: as moments of real lucidity break the surface of the dreamscape, Hôtel Amour is gifted a sudden, but overwhelming sense of coherence in the sharpness of relief: ‘Someone was speaking, and from somewhere a voice found itself and / lifted itself into song’.

More information click here