search

date/time

| Cumbria Times Weekend Edition |

Steve Whitaker

Features Writer

@stevewhitaker1.bsky.social

P.ublished 17th January 2026

arts

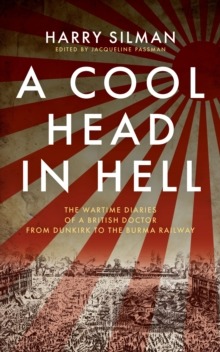

Book Review: A Cool Head In Hell - Harry Silman

In the same captive army was a medical doctor from Leeds called Harry Silman. Silman’s diary accounts of his experiences as a prisoner in Singapore’s Changi barracks, of his experiences on the infamous Burma Railway, and of his earlier service in the evacuation of Dunkirk, have been painstakingly collected and curated by his daughter Jacqueline Passman, into an astonishing document of witness. Published by Extraordinary Books, A Cool Head in Hell is much greater than the sum of its parts: more than a historical narrative, the book is a painstakingly illustrated testament to stoicism and endurance, a resolutely controlled account of unimaginable suffering whose tone is one conspicuous indicator of a species of moral forbearance that seems now to have been lost. Silman’s sense of service is revealed in his own words, not consciously or intentionally, but by virtue of the monumental effort of will those words imply. The generally methodical style of his approach is heavily ironised by what we perceive of the setting, the context of a steamy and turgid landscape packed with rancid intimacies of necrosis and disease. But it is of a piece with the man, who later made light of his experiences, ‘joking about the hardships and privations as if they were mere inconveniences’. The response is not untypical of a group of men and women whose hopes and fears were instinctively subordinated to a perception of duty.

A thorough annotation to an experience underwritten by mass degradation, Silman’s observations are those of a participant. The detailing of a process of a physical and mental attenuation on a huge scale – as a doctor, he is a meticulous recorder of detail – necessarily incorporates the endemic spread of disease amongst the soldiers. The presence of cholera, dysentery and infection in a morbidly, and unavoidably, unhygienic setting, resolves into a nightmare of mud, blood, vomit, faeces and death. More than an observer, the ingenious Silman, who assembles makeshift hospital units and a raddled sense of order and method on the hoof, ministers tirelessly to the sick whilst himself exposed to disease. Jacqueline Passman’s direct and moving narrative interjections give architecture and context to her father’s words, filling in speculative gaps left by deliberate and necessary self-censorship, and bracing the reader for still greater horrors.

The toll on Silman’s own health and ability to function become self-evident and it is an affecting testament to his sense of purpose that he should continue his work whilst himself ill, at one point conducting a ward round whilst being carried on a stretcher. A diary entry of 31 July, 1942, written as Silman was suffering from dengue fever, distils a moment of simple and undiluted compassion:

‘During the dengue do, the other lads were very attentive & scrambled eggs for me & once the Padre cut it up small & kneeling down by my bed, he fed me like a child.’

If Silman sometimes wishes ill on his unpredictable and brutal Japanese captors then he responds with synchronous focus to the random beatings to which he is a frequent witness: ‘I look forward to the day when it will all be repaid with interest’. The reaction is entirely reasonable in the extremity of the circumstances; a desire for retribution sustained in the many who later would feel little pity for the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yet the doctor rarely loses hope, instead maintaining a commendable composure that may be a component of an idiosyncratic optimism; the kind of optimism that embraces humour in times of crisis, celebrates the putting on, in unprepossessing circumstances, of ad hoc concert shows in a jungle clearing, or the creation of liquor in a rudimentary still.

But most, in Silman’s account, we are likely to remember the ‘pluck of these men in such appalling conditions’, the upright bearing of some of those facing the firing squad for attempting to escape, or the commonality of purpose, notwithstanding the lapse of a few into a free-for-all of self-interest. Harry Silman’s description of the symbolic solemnity of a Christmas Day religious ceremony, jointly celebrated by British and Dutch POWs, beautifully conjugates a moment of peace and reflection in a time of turmoil:

‘It looked like a crowded fairground from our position on the balcony. It ended up with the fire ceremony, which is a symbolic affair – the fire represents the spirit of life and freedom which keeps burning, and the Dutch ‘broadcast’ a message to their wives and families in front of the fire, and then each one took a burning rod and lit a candle in his own tent. The association of flame with life is a very common one in many religions. It was quite a dramatic affair, as all the lights were doused, and only the flickering fire played on the announcer’s face as he spoke in a loud voice to the families at home.’

Also by Steve Whitaker...

Poem of the Week: And Then the Sun Broke Through By David ButlerWays of Seeing: Katharine Holmes And Three Generations Of Dales ArtistsPoem Of The Week: Last Christmas Cracker By Steven MatthewsOur Children's Playless Days: Snagged On Red Thread By Jazmine LinklaterEarth, Fire: Notes On Burials By Jayant Kashyap