search

date/time

| Cumbria Times A Voice of the Free Press |

Artis-Ann

Features Writer

12:00 AM 16th August 2025

arts

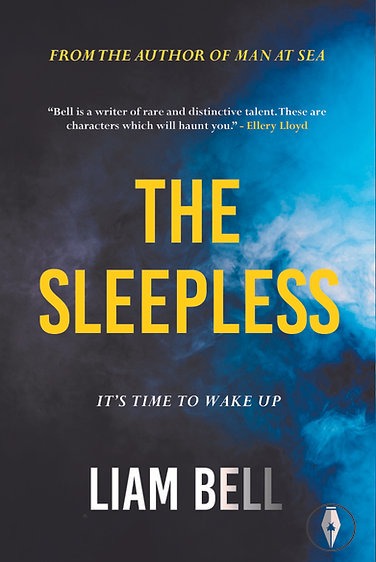

‘Sleep No More’: The Sleepless By Liam Bell

Bell calls this novel a ‘cult thriller’ and Swami Ravi is the leader of a cult which believes we can be trained not to sleep, hence the title. This cult has offshoots all over the world but the focus of this book is the one in a remote area of Scotland.

Tom Grafton is a single dad. Over the course of the novel, we learn that he has overcome the demon drink, something which may have contributed to his wife, Liz, leaving him and their son, Isaac, some eight years previously. She had tried encouraging him to go to therapy, had tried supporting him but ultimately realised that for him to recover, he needed a purpose and that, she decided, was looking after their son. She, meanwhile, took time out for herself and began following the teachings of Swami Ravi. She was to become one of his most dedicated disciples.

Certainly, it is exciting to think about how much more we could do with our lives if we didn’t spend a third of it asleep but it’s not something I think I could ever accomplish.

Grafton finds and gains entry to the commune, meeting its weird (I can’t say wonderful) members. The messianic Joan is devout and leads her people with a spiritual fervour. Eddie and Whippet are less believers, more enforcers who enjoy inflicting the pain necessary to punish those who stray from the true path or who need help to stay awake. Pain is the perfect antidote to giving in to the ‘comforting folds of the duvet and a soft pillow’. Grafton’s investigation is not without pain.

Liz, meanwhile, has returned from India and has heard of the commune in Scotland. She also hears about Isaac’s exhibition and makes her way to it, to meet her son. Together, they travel to Kilchoan. Isaac is worried about the lack of communication from his father who has not made it back in time and Liz wants to meet Joan and to check that the commune is run to Swami’s exacting standards.

Pain is the perfect antidote to giving in to the ‘comforting folds of the duvet and a soft pillow’. Grafton’s investigation is not without pain.

I found the premise intriguing; I didn’t want to stop reading and needed to see how the narrative would play out. Don’t be put off by the violence of the Prologue. It is easy to see how such a movement could sway would-be believers as well as cause alarm for onlookers, how it could attract both the ‘right sort’ and the ‘wrong sort’, the strong and the weak. Nothing is perfect, nothing is pure because humans are neither perfect nor pure. The ambiguity of the ending shows that and ambiguous as it was, it was not disappointing.